Rybia ikra należy do jednych z największych komórek płciowych w świecie kręgowców, jednak procesy i mechanizmy w niej zachodzące nie są jeszcze w pełni poznane. U okonia jedną z zagadek jest wpływ czynników pochodzących od rodziców na jakość potomstwa – larwy. Odpowiedzi szukają naukowcy z Zespołu Biologii Gamet i Zarodka naszego Instytutu.

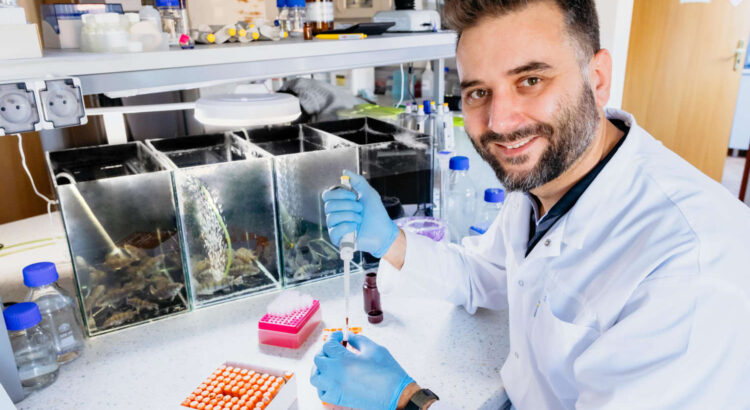

– Na temat wpływu rodzicielskiego na jakość potomstwa u większości udomowionych gatunków ryb wiemy niewiele. W przypadku okonia takich danych w ogóle nie ma. Dlatego szukamy odpowiedzi na pytanie, jakie czynniki ze strony samicy i/lub samca sprawiają, że jedna ryba z ich potomstwa jest jakościowo lepsza, a druga gorsza – tłumaczy kierownik badań dr hab. Daniel Żarski z Zespołu Biologii Gamet i Zarodka IRZiBŻ PAN w Olsztynie.

„PACZKA” Z ZESTAWEM DOŚWIADCZEŃ

Kluczem do poznania tych czynników są badania ikry oraz larw na poziomie molekularnym. Rybia ikra to jedne z największych komórek płciowych w świecie kręgowców – posiada w sobie bardzo dużo różnego rodzaju molekuł, w tym dużo materiału zapasowego (głównie w postaci tłuszczów i protein), który pozwala rybim larwom rozwijać się jeszcze przez pewien czas po wykluciu. Ryby naszej strefy klimatycznej składają bowiem ikrę i w większości przypadków ją niejako porzucają (nie ma tu etapu ciąży jak u ssaków czy też wysiadywania jaj jak u ptaków), dlatego taka komórka, aby się sama rozwijała, musi być odpowiednio zabezpieczona i zaopatrzona „na najbliższą przyszłość”.

Jak w każdej innej komórce, w ikrze znajduje się szereg różnych molekuł poza samym DNA. – My zwróciliśmy uwagę akurat na mRNA, gdzie znajdują się zakodowane informacje, które matka chce przekazać swojemu potomstwu – taki zestaw doświadczeń z całego roku dotyczący m.in. stresu, jaki przeżyła czy interakcji z innymi rybami lub drapieżnikami. Te wszystkie informacje matka przekazuje do ikry, by potomstwo, przynajmniej na początku, było przygotowane na problemy, które mogą je spotkać. Nazywamy to niegenetycznym dziedziczeniem – opowiada naukowiec zajmujący się rozrodem ryb.

Te informacje są łatwo modyfikowalne – matka „aktualizuje” je co roku przy okazji każdego rozrodu. – Między innymi właśnie z powodu czynników, na które samica została wyeksponowana w ostatnim czasie, w jednym roku jej potomstwo będzie lepszej jakości, a w kolejnym – może być gorszej – dodaje Daniel Żarski.

Takich czynników, które warunkują jakość potomstwa – tu rozumianą jako zdolność larw do wyklucia oraz adaptacji do warunków hodowlanych – jest wiele. Nie tylko ze strony matki, ale także ze strony ojca, i wciąż nie są w pełni poznane.

NA PÓŁMETKU

Nad rozwiązaniem tej zagadki pracuje zespół Daniela Żarskiego, prowadząc badania w ramach projektu pn. „Transkryptomiczna i zootechniczna analiza wpływu rodzicielskiego na jakość potomstwa u okonia, Perca fluviatilis”, finansowanego ze środków Narodowego Centrum Nauki (NCN).

– Jesteśmy w połowie projektu. Wykonaliśmy już 4 z 6 zaplanowanych eksperymentów (plus jeden dodatkowy), a warto pamiętać, że badania nad rozrodczością okonia, w naszych warunkach klimatycznych, możemy wykonywać tylko raz w roku – na wiosnę, kiedy ryby przystępują do tarła. Jednym z największych dotąd wyzwań było przeprowadzanie eksperymentu porównującego dwa ekstremalnie różne fenotypy, czyli larwy pochodzące od ryb dzikich, udomowionych oraz ich krzyżówki. Teraz analizujemy zebrane dane, których wstępne wyniki wydają się być obiecujące – wskazuje naukowiec.

Przed badaczami jeszcze m.in. eksperyment, który ma pomóc rozszyfrować, z czego wynika, że potomstwo bliźniacze ma inny potencjał wzrostowy i w efekcie jest różnej wielkości.

– Nasz projekt nie bazuje na konkretnych hipotezach, ale jest projektem eksploracyjnym. Innymi słowy, staramy się zrozumieć te mechanizmy, które zaobserwujemy, a nie „wcisnąć je” w odgórnie założone ramy – podkreśla Daniel Żarski.

Projekt rozpoczął się w 2021 r. i potrwa do 2026 r. Kwota dofinansowania wynosi ponad 2,8 mln zł. Partnerem IRZiBŻ PAN w realizacji projektu jest Instytut Rybactwa Śródlądowego im. S. Sakowicza – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy.

CEL: WYZNACZYĆ STANDARDY

Jak przekonuje Daniel Żarski, wiedza zdobyta dzięki badaniom prowadzonym w projekcie nie tylko przyczyni się do rozwoju nauki w temacie rozrodu i larwikultury ryb okoniowatych, ale też może znaleźć w przyszłości zastosowanie w akwakulturze.

– Okoń jest wdzięcznym gatunkiem do badań z kilku powodów: jest znacznie większy od typowych ryb modelowych, cechuje go duża płodność, jest młodym gatunkiem pod względem filogenetycznym, a do tego ma duży i wciąż rosnący potencjał hodowlany. Dlatego naszym nadrzędnym celem jest wyznaczenie pewnych standardów do tworzenia kryteriów selekcyjnych, zawsze tak bardzo potrzebnych hodowcom – wyjaśnia Daniel Żarski.

Czytaj więcej