Bacteria, yeasts and moulds are unlikely to have good PR, although many of them are useful and used in food production and preservation. After all, without them there is no yoghurt, cheese, pickles, bread, but also cocoa, tea and coffee. Our scientists are involved in research on checking the quality of these microorganisms and the safety of such foods, as well as looking for new strains.

16 October is World Food Day. On this occasion, Dr Anna Majkowska, head of the Microbiology Laboratory at our Institute, takes a closer look at the topic of microorganisms in food.

Although we usually associate micro-organisms in food with either being a potential threat to human health or contributing to food spoilage, many are essential in the production or preservation of food.

– An entire branch of the dairy industry is based on fermentation processes carried out by micro-organisms, with the production of cheeses, yoghurts, kefirs or various types of dairy drinks. Without bacteria, there would be no pickles, which have been around for centuries and are now becoming increasingly popular. Bread and cakes are made with baker’s yeast or sourdough starter containing bacteria and yeast. Cured meats such as salami are also made with bacteria. You probably don’t realise that thanks to fermentation we also have cocoa, coffee and tea. Not to mention a whole branch of wine, beer and spirit production – says Dr Anna Majkowska.

The researcher also recalls that bacteria have been used to preserve food or prepare fermented beverages from milk for centuries, although initially people did not know what was behind it. The conscious use of microorganisms only began with the groundbreaking research of the French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, who lived in the 19th century.

HOW DOES FERMENTATION WORK?

Bacteria ferment, i.e. break down sugars contained in vegetables, fruit or milk (here using lactose) and, on this basis, produce acids (e.g. lactic or acetic) and short-chain fatty acids. This lowers the pH level of the product in question – hence the sour taste of silage. As a result, the product is more difficult to access for undesirable bacteria, e.g. putrefactive bacteria.

– Furthermore, bacteria also produce bacteriocins, substances with antibiotic properties that inhibit the growth of undesirable bacteria such as Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes, for example – adds the scientist.

BACTERIA IN FOOD PRODUCTION

Fermented products – made both at home and on an industrial scale – is mainly based on spontaneous fermentation, meaning that microorganisms naturally contained in fruit and vegetables are used.

The dairy industry, on the other hand, uses appropriately selected strains of lactic acid bacteria as well as yeasts and moulds. – There is a whole spectrum of these so-called starter cultures. We have separate types for the production of yoghurt, drinking yoghurt, kefir, buttermilk, cottage cheese, mould cheese, ripened cheese (those with and without holes – yes, bacteria are also responsible for the holes in cheese) – points out Anna Majkowska.

Researchers are therefore constantly looking for new strains that not only have improved properties needed in the production of a particular product, but also, for instance, reproduce quickly and have additional potential, e.g. as antibacterial agents to combat particular pathogens.

LAB BACTERIA

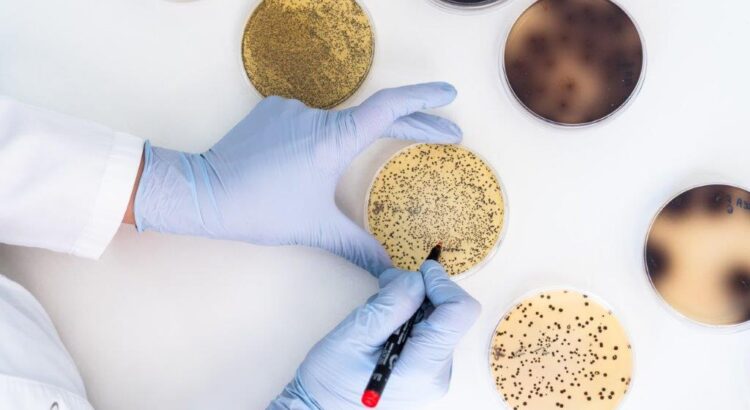

Researchers at the Institute of Animal Reproduction and Food Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Olsztyn are, on the one hand, looking for unique bacteria by isolating them from products that are as natural as possible (e.g. unprocessed cow’s milk or natural fermented products) and, on the other hand, creating new sets of bacteria whose joint action exceeds the potential of each individual (action based on symbiosis).

In the former case, once a particular strain of bacteria has been isolated, it needs to be identified, i.e. assigned to a specific genus and species. It is also necessary to check that these bacteria multiply well (without this, it is not possible to use them on a larger scale) and that they produce sufficient quantities of essential metabolites (such as lactic acid).

In contrast, the work of creating new bacterial combinations (cultures) involves selecting bacteria with the desired properties and testing their subsequent combinations. – Bacteria are like a family – some like each other, others don’t. Therefore, combining one pair results in rapid growth and another in fighting each other. So we test all possibilities, taking many factors into account – she explains.

In the search for new strains, the Microbiology Laboratory scientists place particular emphasis on those with antimicrobial properties, fighting a specific pathogen, such as Salmonella, Campylobacter or staphylococcus.

As Anna Majkowska points out, the demand for the work of food microbiologists is high. – For example, we are currently working with a company that produces health-promoting dietary supplements. We have isolated unique strains with strong antibacterial properties for them – she says.

The Microbiology Laboratory of IAR&FR PAS supervises a collection of approximately 1,000 bacterial strains.

FUN FACTS

- It is bacteria – the main propionic fermentation bacteria – that are responsible for the holes in the cheese.

- It is possible to pickle not only vegetables, but also fruit, e.g. apples or plums (because the base needed for the fermentation process is sugar).

- Pickled cucumbers (and other preserves) have much more nutritional value than raw ones, and are also more easily digested and absorbed by our body.

- Yoghurt contains only two strains of bacteria, while kefir has dozens of them!

- The basis for the production of kefir is the so-called kefir mushrooms/grains, which is a conglomeration of yeast (they are what make the drink slightly effervescent) and dozens of species of bacteria living in symbiosis.

—

Learn more about our Microbiology Laboratory HERE.