Every cell in our body generates an electrical voltage that influences whether it divides, migrates, and forms tissues. Researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences demonstrate that by manipulating this parameter, cell behaviour can be controlled without interfering with DNA.

Every cell possesses a membrane potential — an electrical voltage generated across its membrane. This makes the interior of the cell negatively charged relative to the external environment. “Its value is not constant and depends both on the cell type and on its functional state,” explains Dr. habil. Magdalena Kowacz, assistant professor at the InLife Institute of Animal Reproduction and Food Research, Polish Academy of Sciences.

“Cells that readily divide and have migratory capacity are characterised by a less negative potential — they are depolarised,” the researcher explains. “In contrast, cells that stably perform their functions exhibit a more negative potential.”

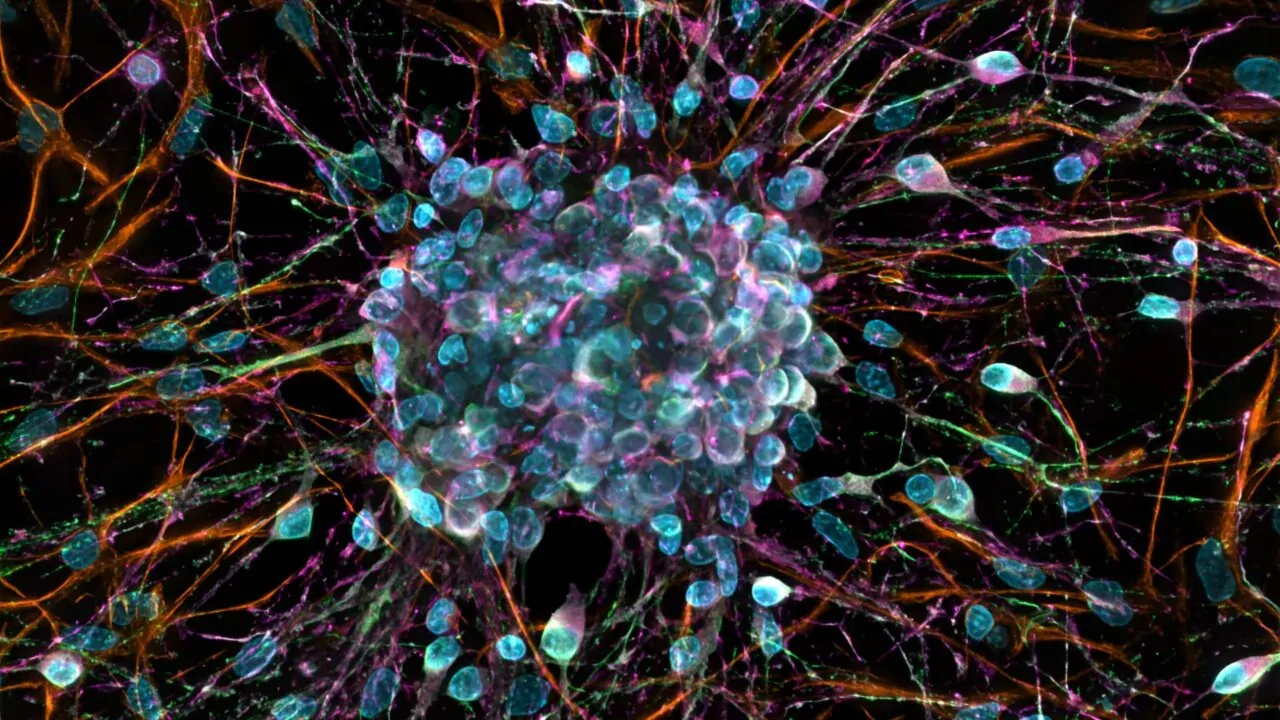

This pattern recurs in many biological processes. “Depolarised cells include embryonic cells, cells involved in tissue regeneration, but also cancer cells,” says Kowacz. “All share common features: rapid proliferation, migration, and the ability to self-organise.”

This observation became the starting point for the research. “We use the cell’s natural membrane potential to control its behaviour,” the scientist emphasises. “If different functional states correspond to different potential values, we can deliberately modify this parameter.”

The study was conducted on chicken embryos, a classical model of vertebrate development. The team focused on a very early developmental stage. “We investigate somitogenesis — the stage at which characteristic body segments common to all vertebrates are formed,” the researcher explains. “At this stage, chicken, mouse, and human embryos develop in a highly similar manner.”

In chicken embryos, new segments form regularly, approximately every 90 minutes. Until now, altering the pace of this process required direct genetic intervention. “We show that this effect can be achieved differently. When cells are depolarised, they proliferate and migrate faster, and the embryo develops more rapidly. Increasing the negative potential, in turn, slows the process.”

Most intriguing is that altering electrical voltage affects genetically controlled processes. “We do not interfere with DNA, yet we regulate a process known to be genetically controlled,” Kowacz emphasises. “By changing the membrane potential, we also influence gene expression.”

Although the research is fundamental in nature, its significance extends beyond developmental biology. Cancer is only one example. “There are diseases of excessive proliferation, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in which resting cells begin to divide again,” the researcher notes.

A similar mechanism appears in Alzheimer’s disease. In this case, cells attempt to re-enter the cell cycle, although the outcome is not proliferation but neurodegeneration.

Dr. Kowacz stresses that this is not a ready therapeutic proposal. “These are basic studies; we are not offering a new treatment method. However, we are adding an important piece of knowledge that may help build future medical solutions.”

Reprinted from Academia, the magazine of the Polish Academy of Sciences.